Diving into An Ancient and Contemporary Practice

SOCIO, ARTS & CULTURES

Freediving, or apnea diving, is not merely a contemporary sporting discipline. Long before the modern feats of champions, civilizations and human communities around the world employed this ancient technique to meet their needs. Whether for fishing, pearl harvesting, or other underwater resources, freediving has been and remains an essential skill for certain peoples. Even today, some of these communities continue this tradition, diving to impressive depths without sophisticated equipment, relying solely on their mastery of breathing and their intimate connection with the ocean.

In this article, we will delve into the history of freediving, its cultural and economic significance through the centuries, and explore the fascinating lives of the Bajau of Indonesia, the Ama of Japan, and the Haenyeo of Korea—peoples who continue to practice traditional freediving.

from blueleaf

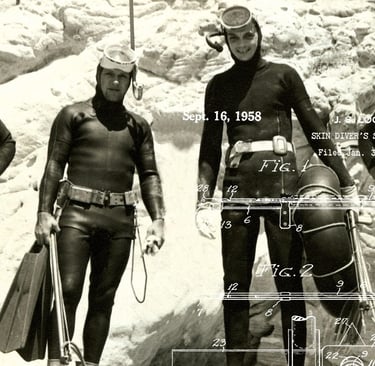

from book of Sonny Tanabe

II. Contemporary Freediving Communities

Despite technological advancements, some coastal communities around the world continue to practice freediving as their ancestors did, sometimes for economic reasons but also to preserve their cultural heritage.

The Bajau : The "Sea Nomads"

Among contemporary peoples who practice freediving, the Bajau Laut, or "Sea Nomads," hold a unique place. This community, living primarily in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Malaysia, is renowned for its ability to freedive to impressive depths, sometimes up to 70 meters, and to remain underwater for several minutes.

The Bajau are traditionally fishermen, and their connection to the ocean is both spiritual and vital. They spend most of their lives on boats or in stilt houses floating above the waters. The Bajau dive not only to fish but also to collect shells, sea cucumbers, and other marine products, which they then sell in markets.

Their incredible underwater abilities have even attracted the attention of scientists. Recent studies have shown that the Bajau exhibit unique physiological adaptations: they have larger spleens than the human average, allowing them to store more oxygen in their bodies during dives.

The Bajau Spleen: A Unique Physiological Capability

One of the most remarkable discoveries about the Bajau is the exceptionally large size of their spleens. A scientific study conducted in 2018 revealed that the spleens of the Bajau are, on average, 50% larger than those of other populations. This phenomenon is crucial in freediving, as the spleen acts as an oxygen reservoir: when a person dives, the contraction of this organ releases additional red blood cells into the bloodstream, thereby increasing the amount of available oxygen. This adaptation enables the Bajau to stay underwater longer than most other humans, giving them an extraordinary physiological advantage.

Mammalian Dive Reflex Enhanced

The Bajau also benefit from a physiological response shared by all mammals, known as the mammalian immersion reflex. This reflex is activated when the face is submerged in cold water, causing a slowing of the heart rate (bradycardia), peripheral vasoconstriction (reduced blood flow to the extremities to preserve vital organs), and, in the Bajau, efficient mobilization of red blood cells through their large spleen. This response allows these divers to maximize their oxygen consumption and extend their ability to remain submerged.

I. The origins of an Ancient Practice

Freediving is likely one of the oldest forms of human interaction with the marine environment. While today it is associated with sporting feats and records, its origins are far more practical. In many coastal regions around the world, freediving was a means of survival, providing coastal peoples with access to the hidden riches of the oceans.

Ancient Greece and Sponge Diving

The origins of freediving trace back to ancient Greece. The inhabitants of the island of Kalymnos, known as the "sponge divers," were renowned for their exceptional ability to descend into the depths of the Aegean Sea to collect natural sponges. The Greeks referred to these divers as skafis, and their exploits were recounted in mythological tales.

These divers used stones as weights to help them descend up to 30 meters below the surface. They could hold their breath for several minutes, sometimes chewing a type of natural gum called chios, which stimulated salivation and helped regulate ear pressure.

The Roman Empire and Underwater Harvesting

During the Roman Empire, freediving became an essential tool for the extraction of pearls, sponges, and other marine products. Pliny the Elder, in his work Natural History, described how divers would plunge to retrieve precious pearls from the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. These divers employed advanced breathing techniques and methods to protect their ears from pressure changes underwater.

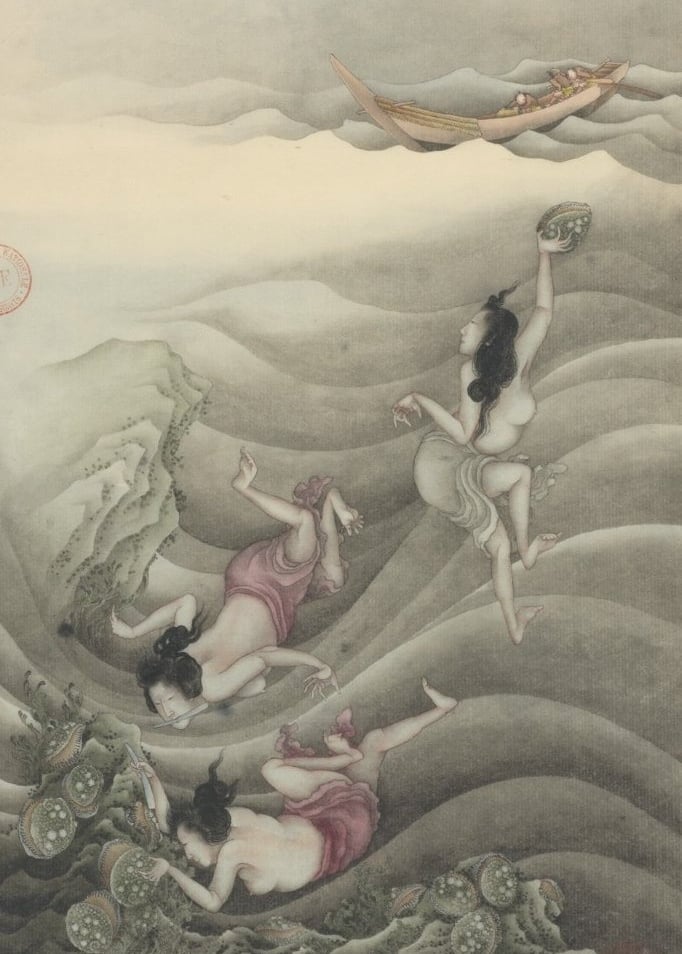

The Amas: The Pearls of the Sea

The Amas, also known as "women of the sea" and historically referred to as "bare-breasted divers," are traditional Japanese female divers who have been practicing underwater harvesting for over 2,000 years. Historically, the Amas dove to collect pearl oysters, seaweed, and other shellfish in the waters of the Japanese archipelago. They can descend to depths of up to 20 meters, holding their breath for one to two minutes.

The work of these women is not only difficult but also dangerous. Diving without any equipment into cold waters demands great physical strength and self-control. Traditionally, the Amas wear a simple white loincloth, believing that this color repels sharks. Today, the Ama sometimes use diving suits, but most continue to dive in the traditional way, without oxygen tanks.

Unfortunately, the number of Ama has significantly declined over the decades, with only a few hundred divers still active, mainly in the Toba region and the Shima Islands. The Ama's way of life is now threatened by modernization and the overexploitation of marine resources.

Impressive cold tolerance

What particularly distinguishes the Amas is their ability to dive in often frigid waters, sometimes without the aid of modern diving suits. For centuries, they wore only a white loincloth when diving, even in winter. The Amas’ cold tolerance is attributed to a gradual adaptation: their bodies have learned to maintain their internal temperature while minimizing shivering, which consumes energy. Some studies suggest that their metabolism has evolved to use energy more efficiently, increasing body heat production.

Breath Control and the « sumbisori »

The Amas also master a unique breathing technique called sumbisori. When they resurface after a dive, they quickly exhale to expel the accumulated carbon dioxide from their lungs before taking a deep breath. This technique is crucial for extending their dive time and avoiding respiratory complications. The sumbisori is not only a technical aspect but also a cultural tradition passed down from generation to generation.

Photo Iwase Yoshiyuki

Photo année 40, Horace Bristol

Photo Yoneo Morita/ Sebun Photo

Maison de la culture du Japon à Paris

The Haenyeo : Age Doesn't Matter!

On Jeju Island in South Korea, the Haenyeo (or "women of the sea") carry on a tradition similar to that of the Japanese Ama. This group of female divers, some of whom are over 70 years old, dives into the cold waters of the Korea Strait to harvest shellfish, seaweed, abalone, and sea cucumbers. Their way of life has shaped a unique matriarchal society, where women are the primary providers of food and income for their families.

The Haenyeo, like the Ama, generally do not use oxygen tanks. They freedive to depths of 10 to 20 meters and can hold their breath for up to two minutes. Traditionally, the Haenyeo learn to dive from a young age, often starting at the age of 12, and continue diving well into old age.

This community of divers has seen its numbers decline significantly over time. While there were once tens of thousands of Haenyeo on Jeju Island, their number is now estimated at around 2,000. The South Korean government has sought to preserve this tradition by inscribing the Haenyeo as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity with UNESCO in 2016.

Endurance Acquired Over Generations

The Haenyeo begin diving in childhood, around the age of 12, and learn to perfect their freediving skills over decades of practice. Unlike the Bajau, there is no evidence that the Haenyeo possess specific physiological adaptations, such as an enlarged spleen. However, they develop an exceptional form of endurance, made possible by a combination of factors such as constant practice, mental preparation, and a lifestyle centered around diving.

The Role of Blood in Oxygen Management

The Haenyeo, like the Ama and the Bajau, also benefit from the mammalian diving reflex. What is remarkable about the Haenyeo, however, is their ability to maximize the use of their oxygen reserves by slowing their metabolism during dives. This allows them to reduce oxygen consumption while maintaining their underwater activities.

Their ability to stay underwater for several minutes, at depths of up to 20 meters, is further enhanced by intense mental preparation. Their culture incorporates meditation techniques and rituals connecting them to the sea, which contribute to their performance and longevity in this practice.

Series of photos by Alain Schroeder

A Little Enchanted Parenthesis

These sublime portraits of "grandmothers of the sea," as he calls them, are the work of photographer Alain Schroeder. He created these black-and-white photographs because he found the black-on-black contrast of the wetsuits against the volcanic rocks visually compelling in his early shots. This led him to the idea of photographing these women against a black background, allowing the smooth, wet texture of the wetsuits to produce a stunning effect in the light.

If you wish to discover more photographs from this portrait series—this is just a small sample—feel free to visit Peta Pixel, where you will also find Alain Schroeder's explanations of his work.

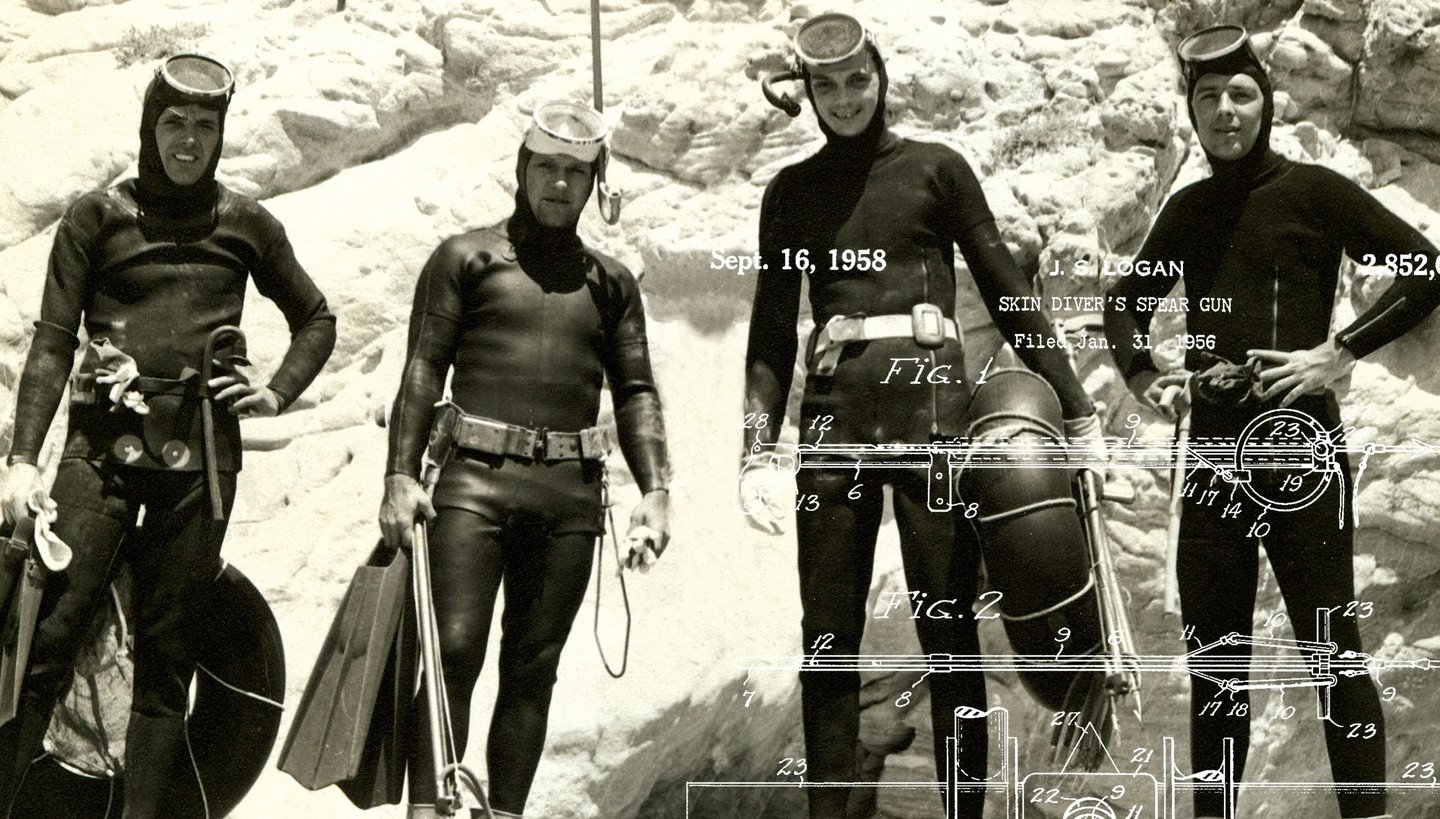

III. Modern Freediving: A Profound Rediscovery

While these communities continue to dive for economic or cultural reasons, freediving has also become a modern sporting discipline, captivating enthusiasts around the world. Freediving competitions, with records for depth or breath-hold duration, have grown in popularity, celebrating the human ability to push boundaries.

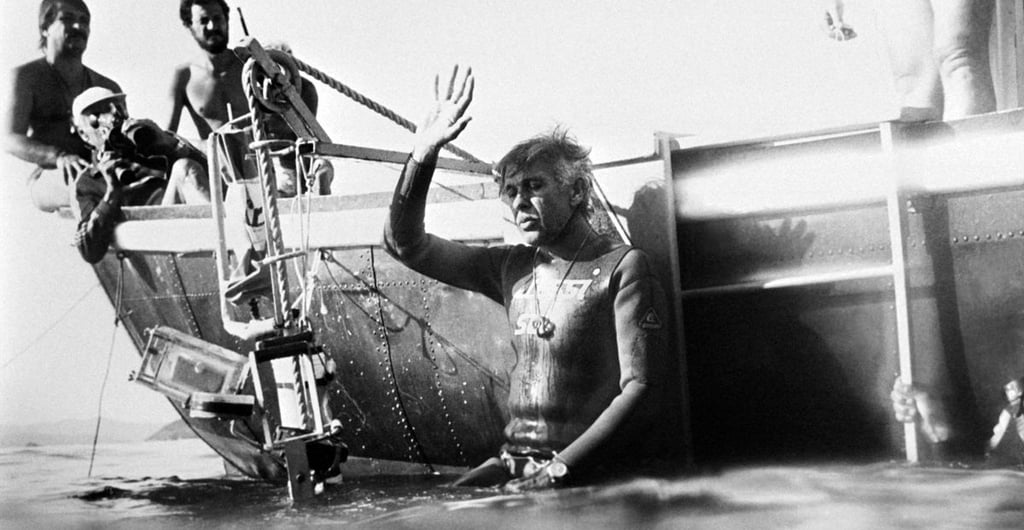

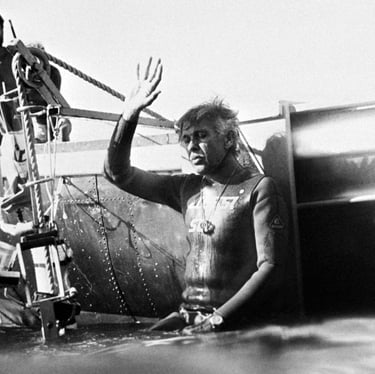

The development of modern freediving is credited to pioneers such as Jacques Mayol, Enzo Maiorca, and later Umberto Pelizzari, who pushed the limits of what was thought possible underwater. These athletes, inspired by ancient civilizations and contemporary freediving peoples, transformed freediving into an extreme sport while emphasizing the importance of connection with the ocean.

IV. The Future of Freediving: A Fragile Balance Between Modernity and Preservation

Although technology today provides ways to dive deeper and longer, traditional freediving remains a valuable practice that deserves preservation. The Bajau, Ama, and Haenyeo embody ancient wisdom and a harmonious relationship with nature, which is fading in our increasingly industrialized world.

Freediving is a living testament to human resilience and our capacity to adapt to our environment. However, threats such as pollution, overfishing, and climate change weigh heavily on the marine resources these communities depend on. It is essential to implement conservation measures to protect both these peoples and the marine ecosystems they help preserve.

Conclusion

Freediving is far more than just a sport or curiosity. For some communities, it is a way of life, an ancestral tradition that connects them to the sea and its resources. The Bajau, Ama, and Haenyeo are living examples of this practice, embodying both the challenges and the beauty of life in symbiosis.

Jacques Mayol during a No Limit dive